Okay, maybe not completely wrong, but in the field of biomimicry plagiarism is not only accepted, it is encouraged! Biomimicry is an emerging scientific discipline where the earth is the author and we are her readers, who freely take lessons from her pages.

In her book Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature, Janine M. Benyus defines the field as "the conscious emulation of life's genius."Biomimicry is a recognition that as hard as we humans try, the earth has a few billion years of product and process innovation on us. And thus, there is an endless supply of time tested inspiration available to us if we connect our understanding of biological practices to the design process.

So, what's the point? From one-off product ideas to solving societal problems, nature offers (excuse the pun) a WORLD of insights perfectly fitted for any design challenge.

The basic:

In its simplest form, biomimicry provides us with ideas from existing biological forms to apply to every day items - as seen in this handbag by designer Christian Louboutin (Source: Style Guru).

The advanced:

In its more advanced forms, biomimic principles are used to explore solutions to some of life's most complex problems - including population issues, energy shortages and global health pandemics.

Here's an example of how we might use lessons from salmon runs to rethink how we approach large population migrations (ie: traffic congestion):

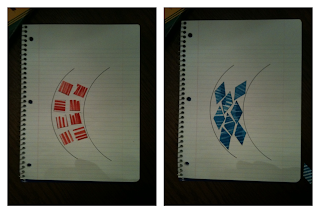

On the left is a rough sketch of a road with eight cars traveling through a bend. We've all been there; square shapes do not do well outside of straight lines. Enter biomimicry. Where do millions of things pass through a narrow space at one time? Salmon runs!

On the left is a rough sketch of a road with eight cars traveling through a bend. We've all been there; square shapes do not do well outside of straight lines. Enter biomimicry. Where do millions of things pass through a narrow space at one time? Salmon runs!

So, what if we traveled in vehicles that mimicked the shape of a fish (like the picture on the right)? Perhaps we could fit more people in less space while reducing other costly inefficiencies, like drag.

Here's an example of how architects are currently using biomimicry to create more efficient office buildings.

This is a picture of the Eastgate Centre, in Zimbabwe. Designers modeled the cooling system after termite mounds. This natural approach to ventilation saved $3.5 million in energy costs during its first five years of operation according to an article from the Boston Globe (2010).

Nature has already answered many of the most complicated design questions for us. And though we've been observing that work for at least the last ten thousand years, observation alone is useless.

Action requires translation. That's where I come in. I'm not a biologist, nor am I an engineer or design type. I'm good at making connections and explaining opportunities in simple terms, which is exactly what is needed in this budding discipline.

The opportunity is real; and unlike any other author, the earth is asking you to take her thoughts as your own. Plagiarizer away, my friends.

No comments:

Post a Comment